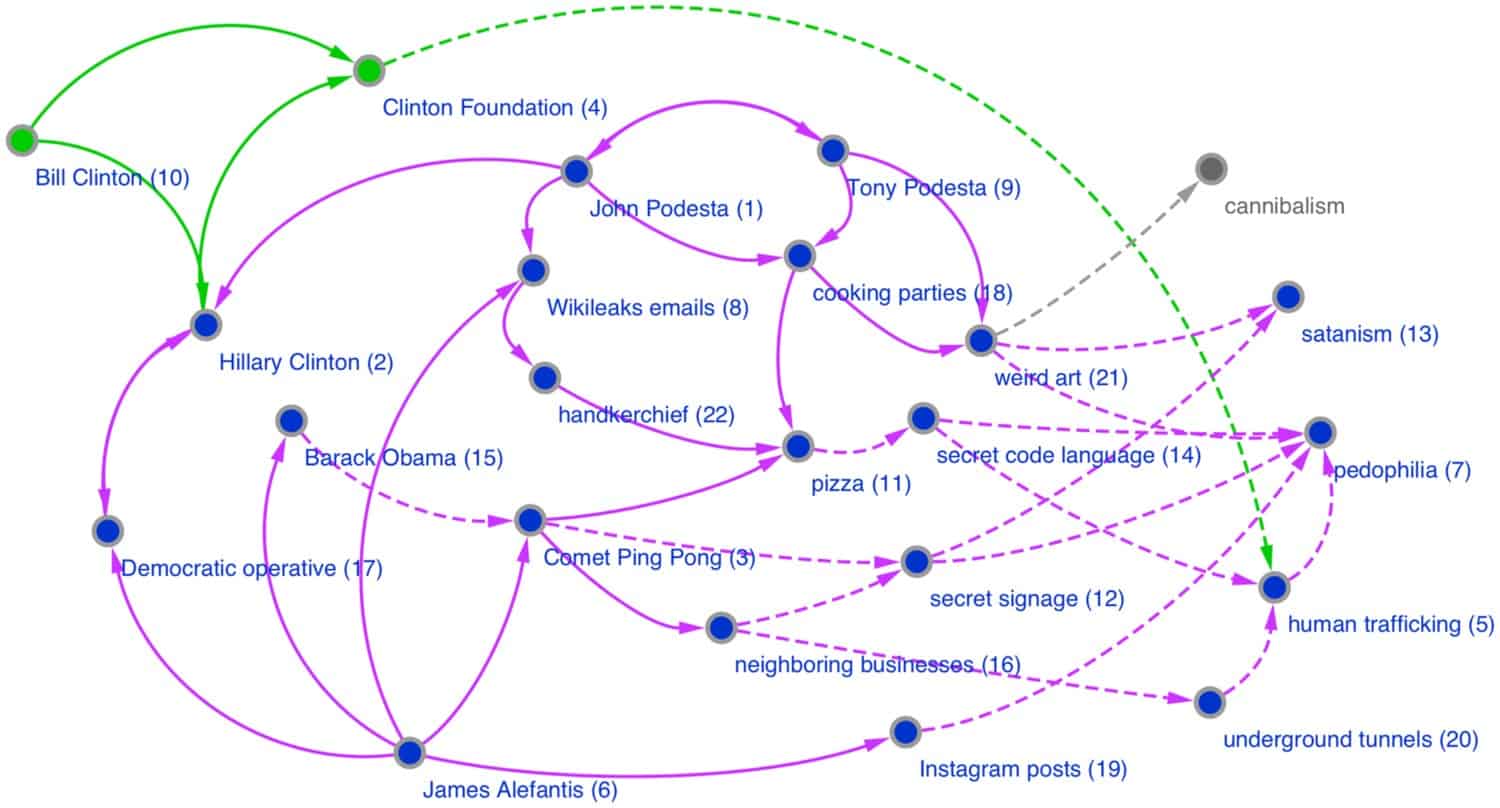

Case Study: Riding the Coattails of Conspiracy

In 2020, folklorist Tim Tangherlini and his collaborators published an article on how narrative frameworks could help people distinguish between conspiracy theories and real conspiracies. Within months, his research was being written about and talked about by the BBC, Ars Technica, Axios, the Conversation, and NPR’s “Science Friday,” to name just a few. How did he get so much national coverage? Tim likens it to surfing: being in the right spot at the right time to ride the wave all the way in.

But his success was also built on groundwork begun much earlier. In this 7-min video (below), Tim Tangherlini talks about what he did to get his research out into the public eye. As an academic folklorist in a university setting, Tim established a strong and collaborative relationship with the staff of the press office at his school. Whenever they needed someone to speak about a folk tradition such as an upcoming holiday, he always made sure to say yes. He also made sure to keep them apprised of his current research in case they identified any useful media connections. When he had research that he thought would have general appeal, he approached these folks and pitched his idea. Because he established a strong relationship with them, they were much more amenable to helping him promote his work. In this video, Tim also discusses the importance of preparing a brief, jargon-free explanation of your work, and seeking opportunities to collaborate and present across fields to encourage the sharing of ideas and research in ways that can be understood by general audiences.

Despite our best efforts, we do sometimes make mistakes and are happy to correct any errors that you may come across on our site. Should you find an error, please submit one via the “submit a correction” link.